The Monolithic Media

A journey into the singular/plural rabbit hole(s)

By Evan Meade, 2021-04-27 06:49:00

This past week, I fell down a weird research rabbit hole trying to figure out whether “the media,” in the sense of mass communications or the press, is a singular or plural noun. I still can’t really explain why I had to know, except that I was recently reading Philip E. Tetlock and Dan Gardner’s phenomenal book Superforecasting, when a particular sentence struck me as odd:

“A confident yes or no is satisfying in a way that maybe never is, a fact that helps to explain why the media so often turn to hedgehogs who are sure they know what is coming no matter how bad their forecasting records may be.” (pp. 138)

The phrasing subconsciously struck me as odd. In my mind, it would be far more natural to say “the media so often turns” than “the media so often turn.” Turns out, it’s one of those topics where grammar scientists claim there is a “correct” answer, but a large portion of the public does the opposite anyways. In fact, I found one post from 2007 claiming it is plural, only to have the same blog essentially concede the battle against singularity in 2010. But that still doesn’t answer my deeper question. Why was it that I considered “the media” to be singular rather than plural? An actor instead of a group?

My initial hypothesis was that in light of increasing political polarization, people increasingly paint media and journalism with a broad brush. Condemnations of “fake news” and “bias” in the media suggest that journalists act in a united interest. In the context of such public debate then, it seems reasonable to treat “the media” as a singular noun, since it is a united actor. Yet in another (perhaps more idealistic) perspective, the media is made up of a range of publications with disparate agendas, which would more naturally imply the term is plural. While I hardly feel qualified to assess the degree to which either of these philosophical views is true, I can certainly try and track public perception of the media over time. It was a bit tricky, but I wanted to know how much the public perception of the media’s uniformity was actually changing over time, and how much was simply being reflected to me by my filter bubble. And for that, I needed a large, fairly representative dataset.

Data Collection

Google Ngram is a wildly ambitious project by Google to map the usage of written words over time. Collecting primarily from books and other written media dated as early as 1800, Ngram allows anyone to see the relative popularity of words or phrases in any particular year. The question then, was how to formulate my question in a way that Ngram could understand?

First, I had to identify synonyms for “the media” which could reasonably be interpreted as either singular or plural nouns. After some dictionary references, the only candidates I could come up with were “the media” and “the press”. Other terms, like “journalists” or “reporters,” are too clearly singular or plural to imagine many meaningful trends in their perceived singularity/plurality. One term that I reluctantly decided not to include was “the news,” because it seemed far more likely to appear in reference to an arbitrary piece of information rather than the institution of journalism (ie. “did you hear the news about Megan’s baby shower?”). Since Google Ngram can’t tell us the author’s intention behind each usage of a particular word, we can only guess as to the actual extent of this noise. Thus, we are left with two terms to track: “the media,” and “the press.”

Based on knowledge from that 2007 blog post, I opted to select data from 1919 onwards, since this was right around the earliest known usage of “media” in the sense of mass communications.

Media vs. Press

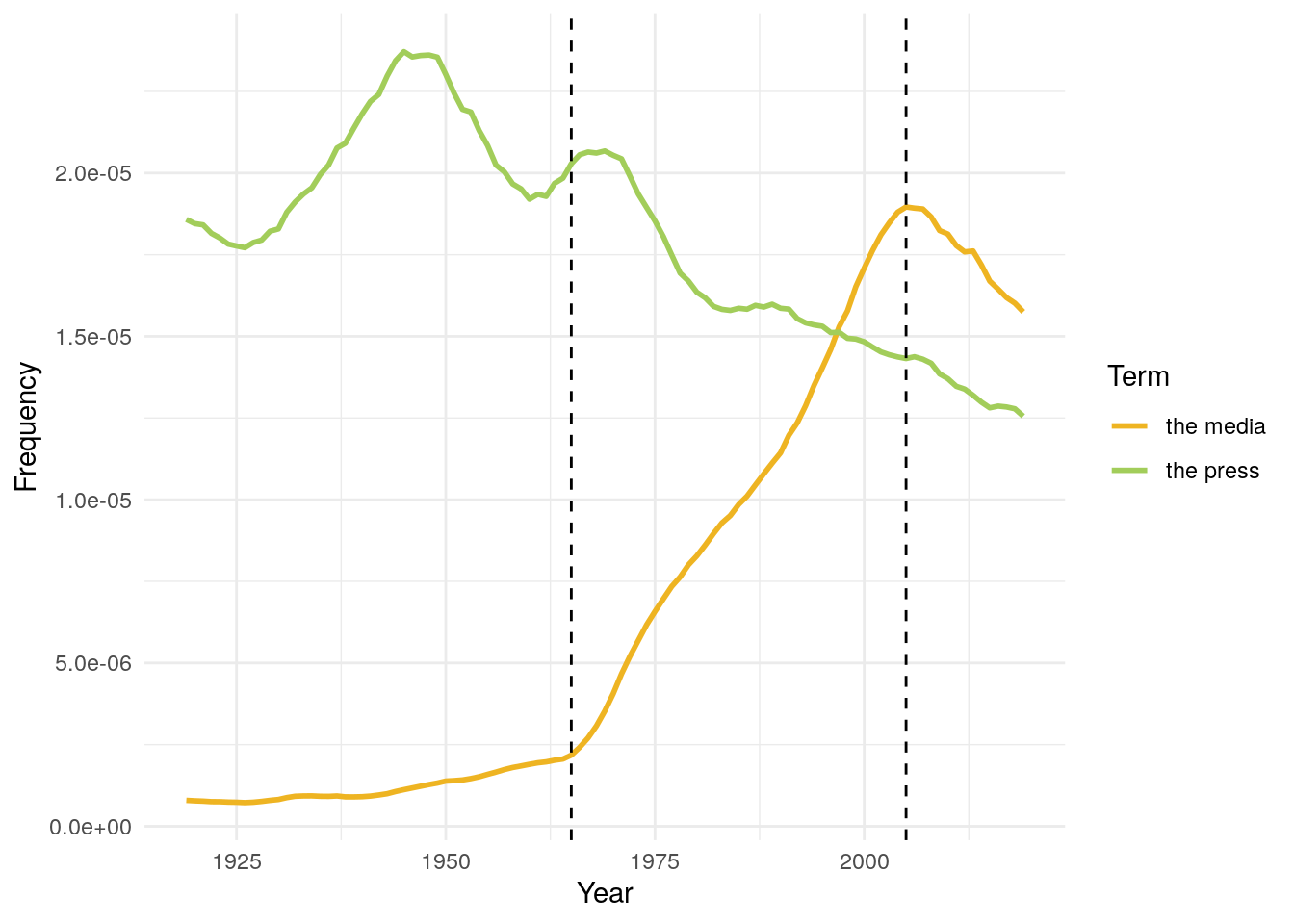

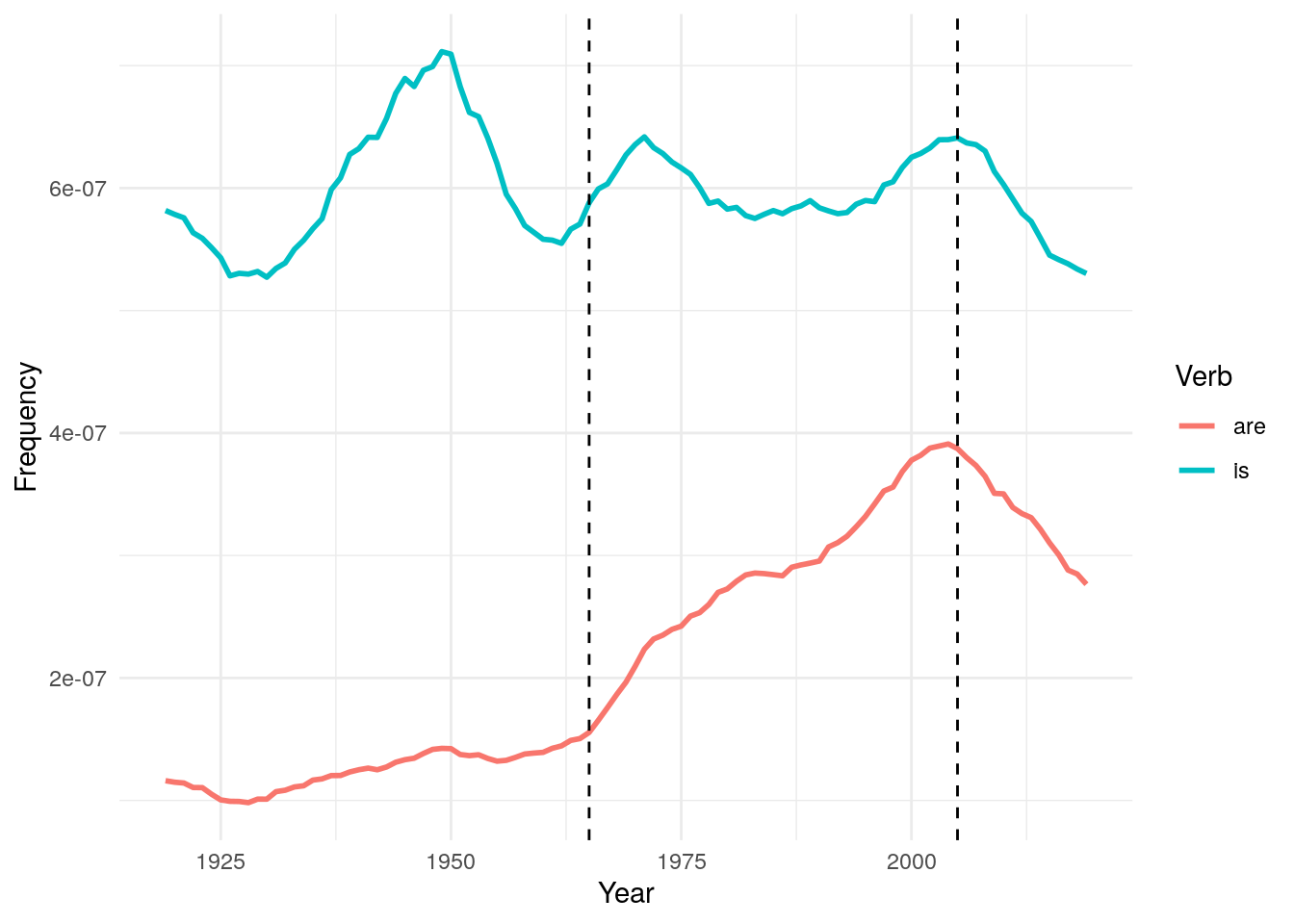

Here we see the usage frequencies of “the media” and “the press” from 1919 to 2019. To better highlight the trends, I used a smoothing factor of 3, which means each year’s frequency is actually the average of the actual frequency as well as those frequencies within three years of it. So, the value for 2000 is the average of years 1997 through 2003.

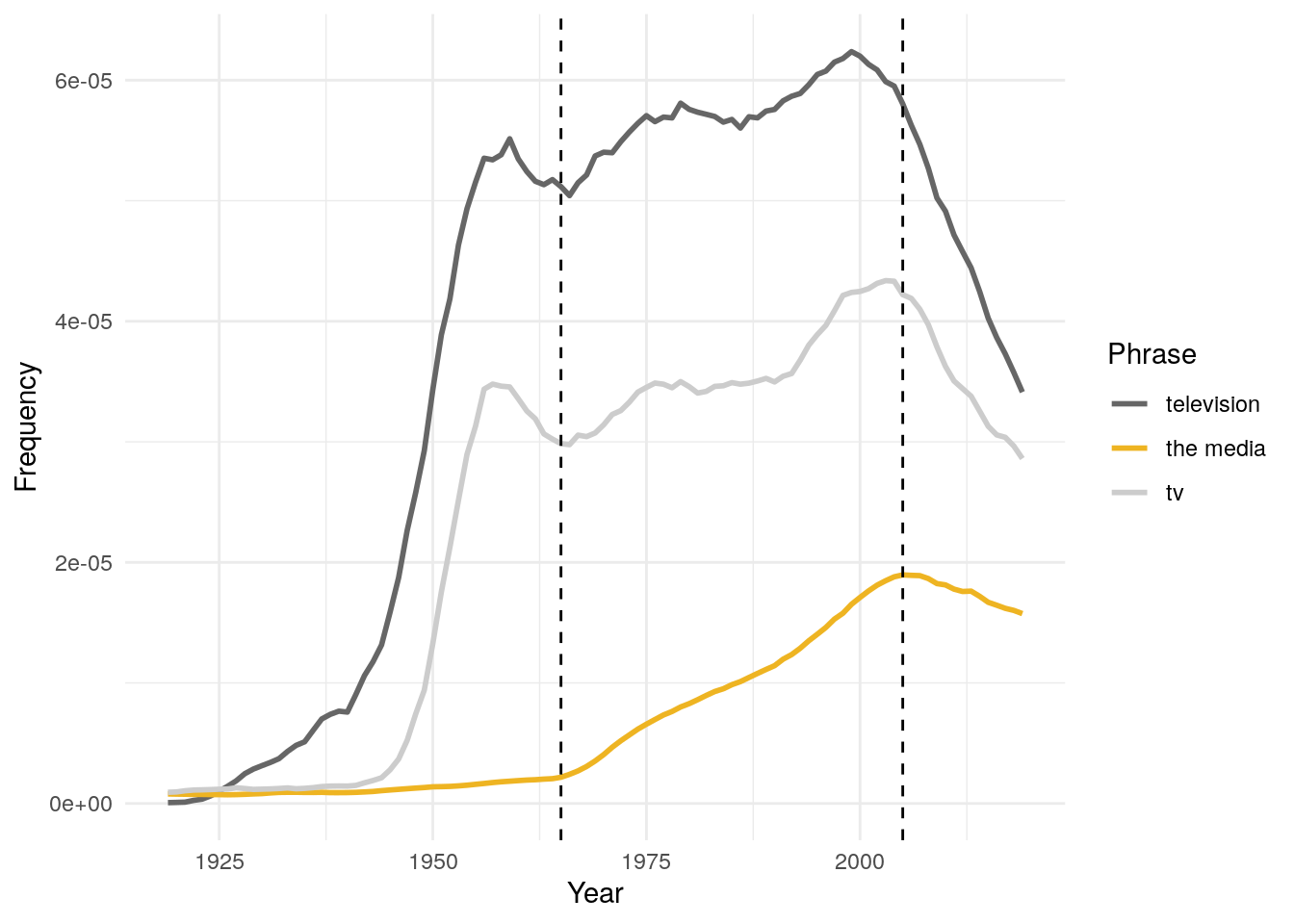

Around 1965, we can see a decided uptick in usage of media, coupled with a downtrend in usage of press. This inverse behavior, while not perfectly complementary, can give us some confidence that we selected good synonyms, as media presumably begins to replace some of the usage of press. Almost thirty years later, near 1997, the term media overtakes the term press for the first time, and still remains higher, though both terms have been on the decline for the past 15 years. As for what accounts for this sharp rise, we can’t be sure. My initial hypothesis was that it correlated with the explosion of television, as the rise of news channels may have shifted perceptions of journalism away from newspapers and the physical “press.”

While these trends do not perfectly correlate, they rise at similar rates over similar time periods, which means it’s still a very plausible theory. Regardless, we see the trend over time of “the press” increasingly becoming “the media.” If I were a ’70s detective with a corkboard wall covered in red string, I would put a big pushpin in this graph; it’s our first clue in unraveling the shifting perceptions of media’s uniformity.

Singular or Plural?

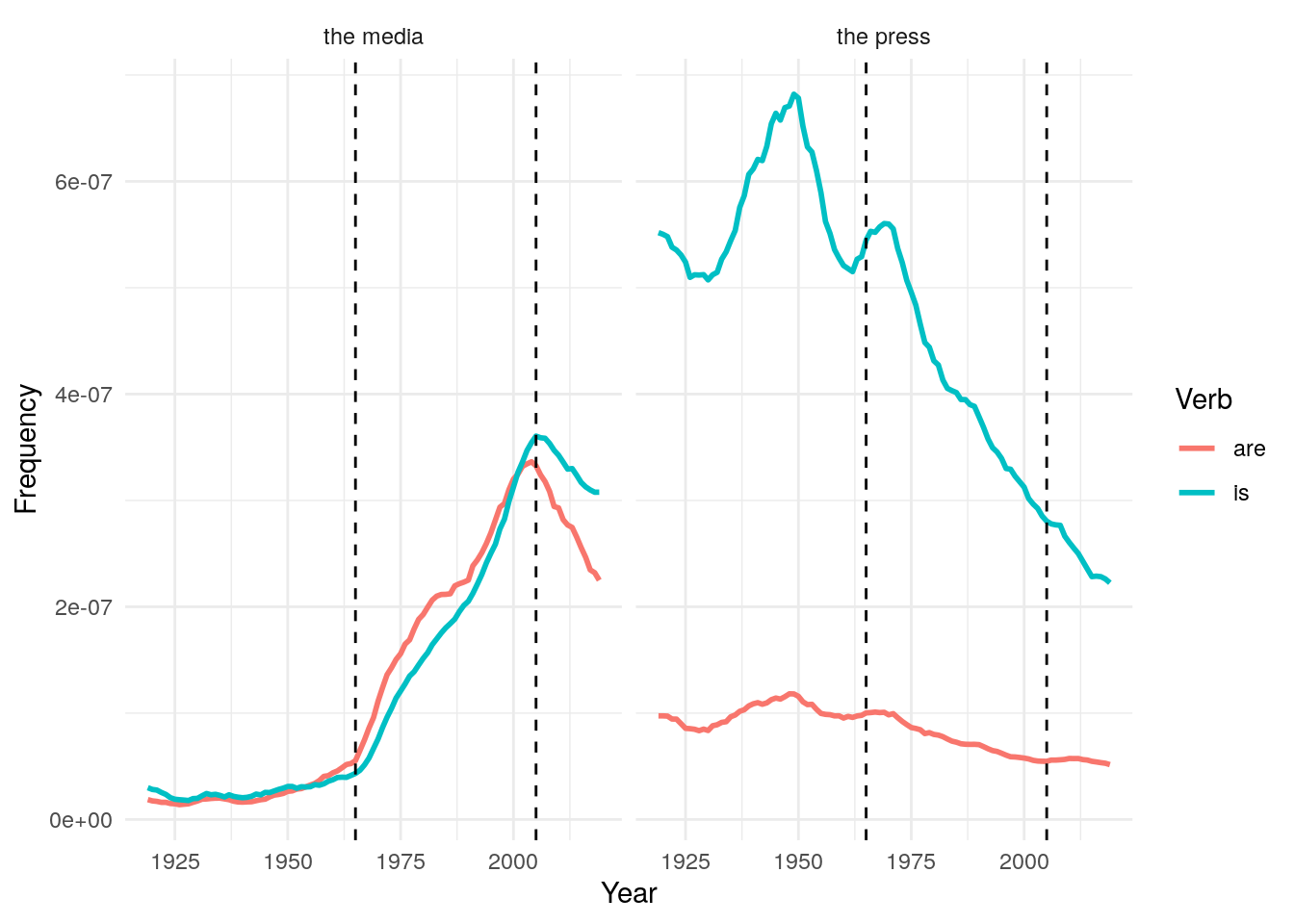

Now that we have the background out of the way, let’s return to our initial question. Is “the media” singular or plural? Though there is no perfect way to test such a high-level query (ie. I don’t know enough about natural language processing to figure it out), we can use a simple trick to approximate a solution. All we have to do is track usage of “the media is” and “the media are” over time. With any luck, these frequencies should be proportional to usage of each term as a singular or plural noun.

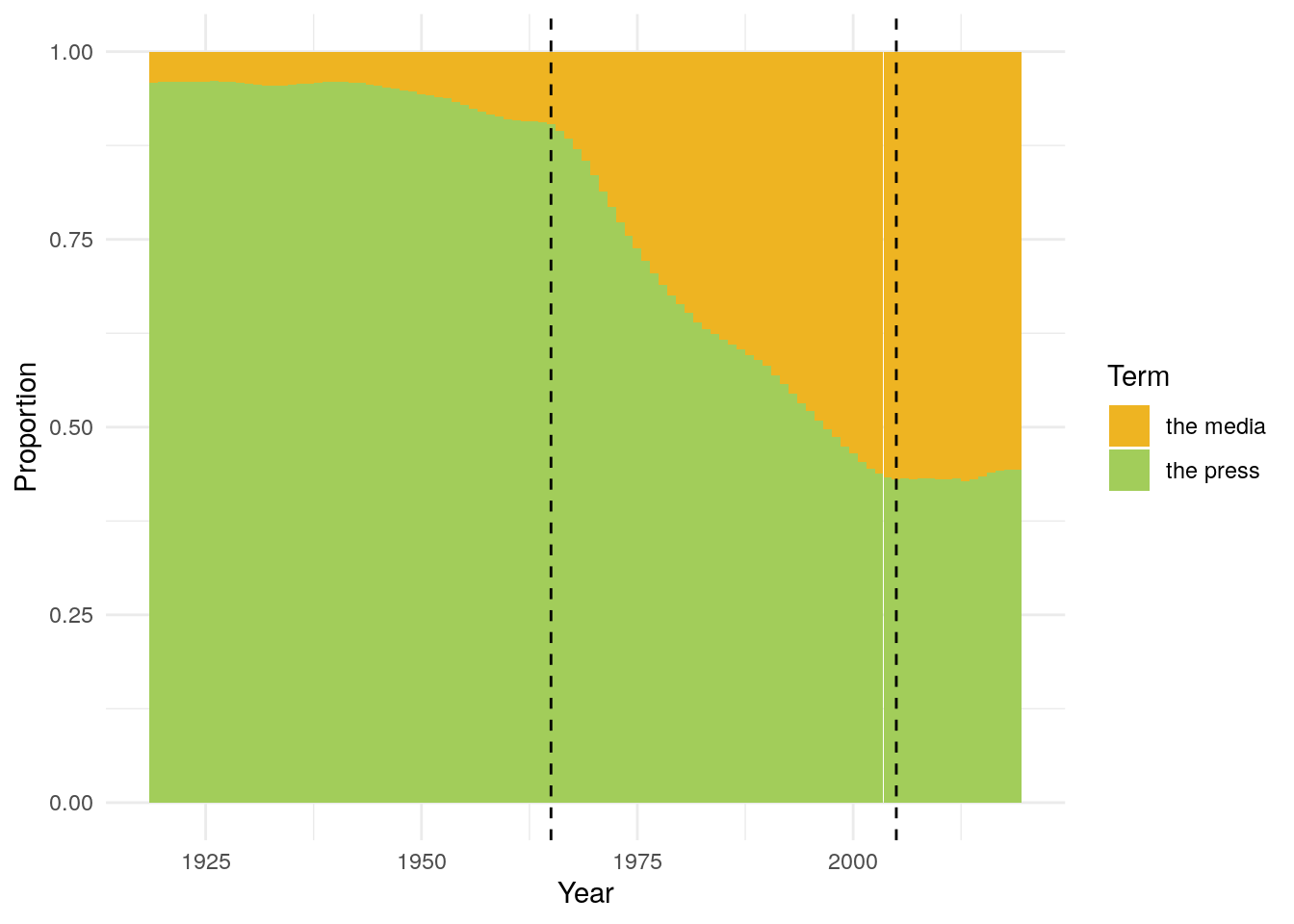

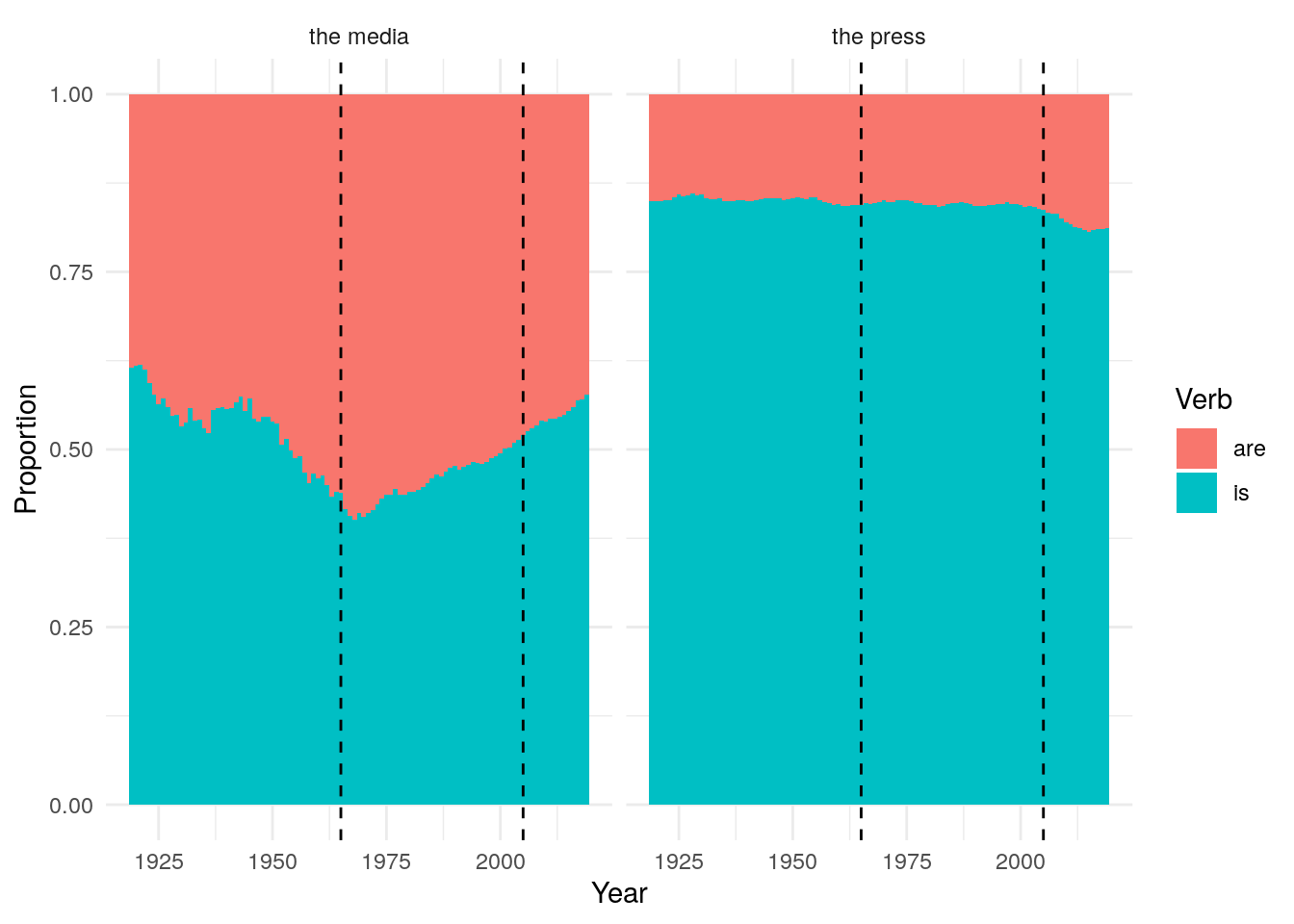

Right off the bat, looking at the line charts, we can see that the media’s singularity or plurality has always been a contentious question. Especially prior to 1965, usages of “the media is” and “the media are” are almost even. That means people were using “the media” as a singular about half the time and a plural about half the time. During the period of media’s growth, “are” takes a slight lead, but since 2005, “is” seems to be taking an increasing lead. In fact, if we look at the proportion charts below, we can see that that is exactly the case. “The media is” has been on a steady increase since 1965, crossing the 50% mark right around 2005, shortly before those blog posts resigned themselves to the term’s singularity. The singular media trend continues to this day, now approaching 60% of usage, with nothing on the horizon capable of halting its relentless onslaught. Apparently I am already a casualty of this statistical skirmish.

But why is this change happening at all? What happened starting in 1965 that could account for this pronounced trend that flipped usage of “the media” on its head over the past 50 years? Well, as we established earlier, that was when “the media” began replacing usages of “the press.” And as we can see in the press’ proportion chart, that term has always been decidedly singular. Indeed, it has almost always been used with “is” (~85% of the time) rather than “are” (~15% of the time). So it seems reasonable to assume that as the media begins to replace the meaning of the press, its usage increasingly reflects the press’ singularity. While there was a slight dip in press singularity around 2010, it is not clear if this is even significant, as even then “is” accounts for ~80% of usage. And so, while the line chart for the press may appear to indicate dramatic change in usage, when you correct for the term’s declining popularity overall using proportions, the effect disappears.

Sidenote: This is yet another warning that a number in isolation will always try to trick you. Any good statistic requires at least two numbers: one to communicate the value of interest, and one to which the first value can be compared. Think of it like units on a measurement. When we say “6 miles,” the “6” represents the value of interest, and the “miles” provides a scale for that value. In the same way, the declining frequency of “the press is” appears to indicate increasing plural usage of the term, but in reality, the term is just declining overall and plural usage is relatively constant.

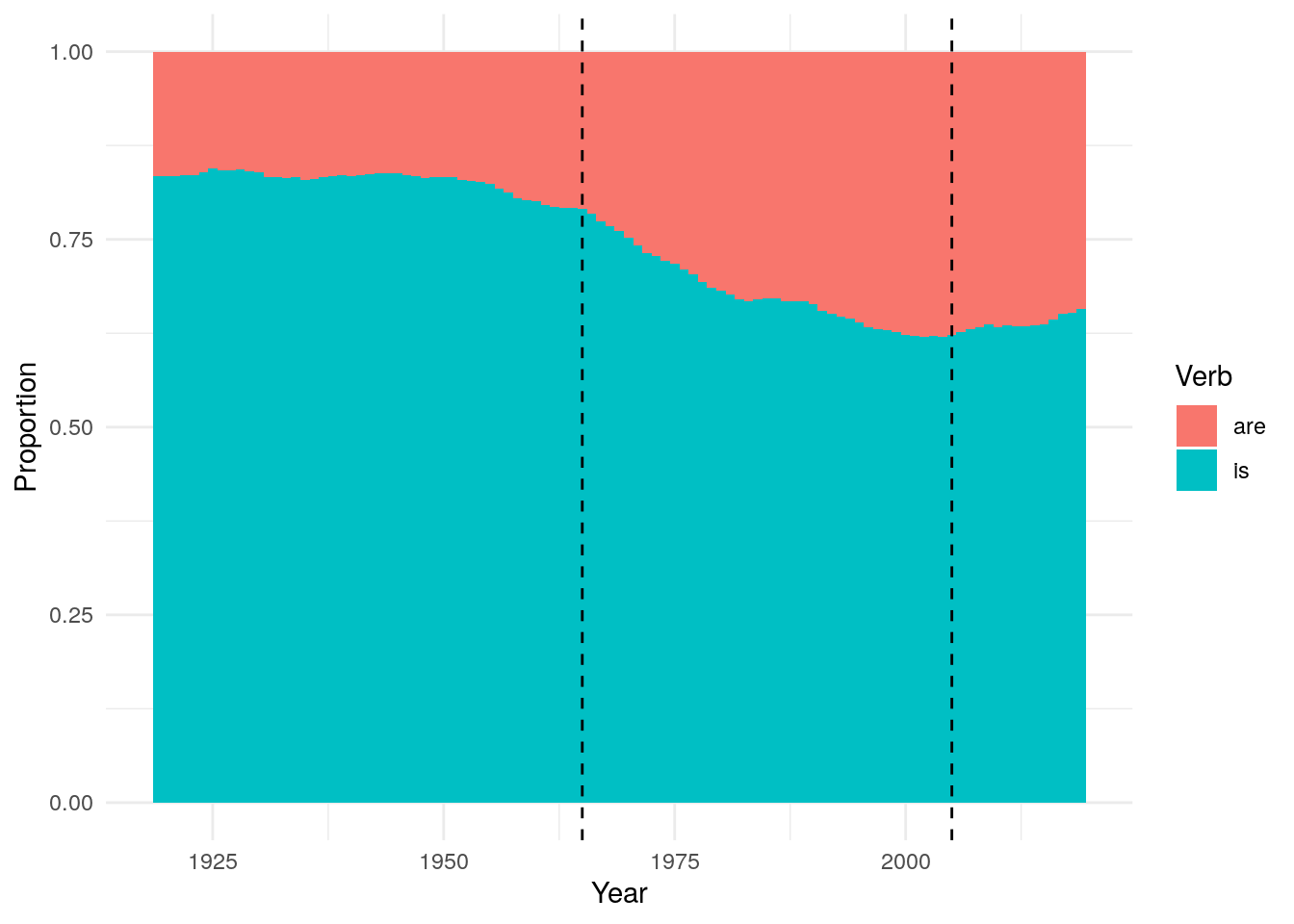

And so, without further ado, we can combine the press’ and the media’s frequencies to find whether their overall usages are singular or plural. Once again, that period of TV’s growth contains the most dramatic change as “are” shifts from less than 25% of usage to almost 40% of usage. Likewise, this trend begins slowly reversing after about 2005. When combined with the previous plots showing the consistent increases in the singular media, a possible story begins to present itself. I think we finally have the critical piece in the puzzle to describe once and for all how usage of “the media” has changed over time.

Conclusions

Prior to 1965, journalists and the news were referred to almost exclusively as “the press,” a term which was predominantly used as a singular noun. Why exactly the press was believed to be singular is not yet clear to me. That being said, with the popular explosion of cable TV in the 1960s, the public’s perceptions of news changed, as they increasingly got their information from a wide array of television channels. The move from physical papers to TV screens shifted usages of “press” to the more modern and technologically inclusive term “media.” Meanwhile, the novel diversity of cable channels accounted for journalists increasingly being referred to in the plural form. What is less clear is why these trends began reversing themselves around 2005. While growth of “the media” has stalled, it is increasingly treated as a singular noun. This may be a sort of delayed correction to mirror the traditional usage of “the press” as singular, or it may somehow be connected to yet another media shift: the rise of online news. However, such a hypothesis would require further research.

Taking this all into account then, it seems that my tendency to refer to “the media” or “the press” as a singular noun is actually the historical norm, and not necessarily a product of increased political polarization in the media’s portrayal. While that is a relief in some ways, it is also a brutal reminder of just how deeply political language can insert itself in my worldview. What does it say about me when my first explanation for a grammatical quirk is partisanship? What does that say about society in general? Probably nothing good to either of those questions. While this exploration revealed some interesting tidbits of knowledge, my main takeaway is to try and step back from problems more often, analyze objective data, and come to a rational conclusion rather than accepting my initial reaction as a conclusion. Incidentally, this is one of the key points made in Superforecasting, the very book that spawned this whole mess. I suppose you could call this post an unintentional tribute to the forecasting principles contained therein.

In short, the media killed the press, and I have spent almost eight hours researching the intricacies of subject-verb agreement. Send help.

Data Science

R Google Ngram Linguistics